Lost in the crowd: Transition to university life poses challenges for student veterans

Clarification: In a previous version of this article, Drew Shapiro’s housing payment was unclear. The money came partially from out of pocket and partially from a stipend through the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Drew Shapiro slept on a mattress on the floor of a Columbus Avenue “slum house” for half of his first semester at Syracuse University. He made most of his meals in a single serving rice cooker surrounded by the stench of raw chicken his roommates left on the counters. Shapiro, a 27-year-old United States Air Force veteran, couldn’t afford to regularly buy common items like eggs as he paid his $280 per month rent partially out of pocket and partially from a stipend provided by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Integration proved difficult, as few skills Shapiro acquired in his eight years of service as a flight loadmaster and security worker from Frankfurt to Baghdad translated to civilian life.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs programs designed to fund Shapiro’s education didn’t kick in immediately, leaving him struggling to cover basic living costs amid lingering mental issues.

“By the end of my first year in school I was ready to just end my life,” Shapiro said.

Life has gradually improved for Shapiro, a photojournalism and Middle Eastern studies major who will graduate in May. The VA eventually distributed benefits to Shapiro – including tuition and disability aid – giving him financial security and medical care to manage anxiety, insomnia and depression caused by post-traumatic stress disorder.

The isolation and helplessness Shapiro felt upon entering civilian life is not unique.

Many veterans continue to struggle in their transition to civilian life, so much so that Mike Haynie, founder of the Institute for Veterans and Military Families, addressed the mental illnesses and identity issues veterans face in a Feb. 3 TEDx talk at the University of Nevada. Even at SU, which has been ranked a top military-friendly school, veteran students can fall through the cracks.

“I was treated like any other undergrad,” Shapiro said. “No one even lifted an eye.”

Under the GI Bill, the VA funds higher education for former and current servicemen and women. The VA supplies up to $19,198.31 for tuition costs and provides a housing allowance for students attending private universities in the 2013-2014 academic year, according to the VA website. With SU tuition around $38,000 per year, the university and the VA both contribute to fund the remaining veteran tuition through the Yellow Ribbon Program, Shapiro said.

But when Shapiro left the Air Force in May 2011 and enrolled for the fall semester at SU, he didn’t receive housing or Yellow Ribbon benefits, he said. He’s not sure where exactly he, the university or the VA erred in the process. Shapiro was referred to the financial aid office and ended up taking out student loans, for which he still owes $27,000. He said the VA currently has made no arrangements to pay back the loans.

“I shouldn’t have had to have student loans at all,” Shapiro said. “Everything should have been 100 percent absolutely covered.”

Currently, 188 veteran students at SU receive benefits, said Keith Doss, veterans’ advisor at SU’s Veterans’ Resource Center. The center serves as a liaison between veteran students and the VA, resolving paperwork and eligibility issues, Doss said.

The center helped Shapiro apply for Social Security disability benefits in 2013 and might have been able to resolve his tuition benefit issues early on, but Shapiro said he received little information on the resources available to veterans. Shapiro said he didn’t understand the extent of the school’s programs, which Doss said included counseling and outreach services, until his second year.

Shapiro said he has received emails tailored to veterans since coming to SU, but a lack of information from the university may have contributed to his financial woes.

Shapiro continued to scrape money together to pay for his education. By fall 2012, he was living in a house on Euclid Avenue. His roommates would drink late into the night and sell drugs out of their rooms, which amplified Shapiro’s already aggravated insomnia and anxiety from then-undiagnosed PTSD. He said he drank often and took over-the-counter medications in large doses during the semester.

But by the start of the spring 2013 semester, the VA had recognized Shapiro’s case and he started to receive pay and military disability checks. By August, he started receiving Social Security disability payments, he said.

“I went from being totally broke and ready to kill myself, to being able to scrape by to now, I’m fairly comfortable,” Shapiro said.

Financial problems and few job opportunities can make veterans feel more disconnected from their identity and their surroundings, said Dan Savage, chief of staff at the IVMF. The organization, launched with SU’s help, is one of the nation’s first multidisciplinary veterans’ research institutions. It works to ease veteran reintegration, said Savage, who is also an army veteran.

IVMF trains entrepreneurs online and in-person in hopes that veterans will start their own businesses, Savage said. It also emphasizes consumer education so that veterans will make informed financial decisions when they return to civilian life, he said.

“One thing that we find is that veterans don’t always know the opportunities that await them,” Savage said. “Sometimes they don’t know what they might be qualified for.”

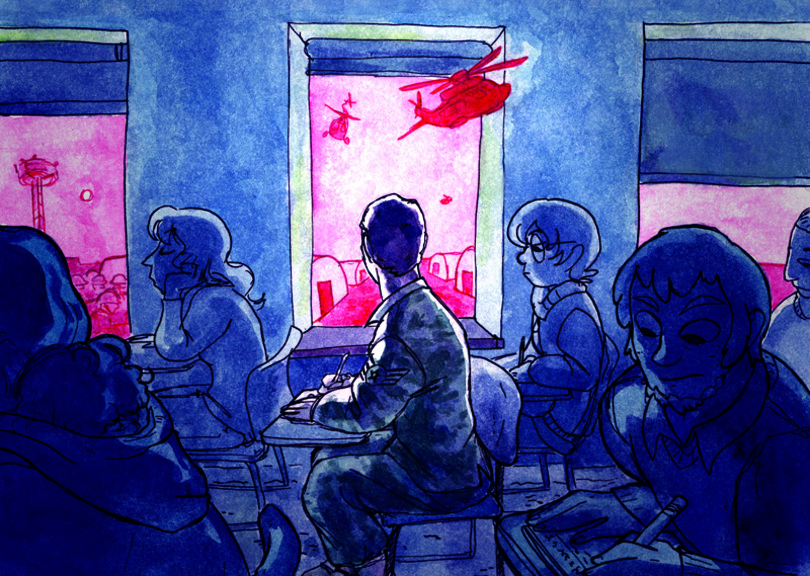

Since Shapiro resolved his financial confusion, he said his life has mostly stabilized. The hairs on the back of his neck still stand up when he hears the whirring of helicopter blades and one time, he ducked out of class when he heard music with Arabic lyrics.

But Shapiro said his life at SU has improved greatly. Currently, he lives in his own apartment with a Rottweiler and pit bull mix named Athena, who he calls his “battle buddy” or “suicide prevention dog.”

He hopes to take a year off after graduation to work on an independent photo project before going to graduate school, he said.

And for the first time since leaving the military, Shapiro sees potential for himself, a far cry from the first-year student that contemplated suicide from a mattress in a beaten down house.

“For the first time, I see a future,” he said. “I think there’s a future out there for me.”

Published on February 10, 2014 at 2:00 am

Contact Jacob: jspramuk@syr.edu